Noirs I Have Known

This month I'm watching noirs. I've always loved the aesthetic of noir without actually immersing myself in it, and I don't consider this a failing; noir never went away, and you can understand its conventions without watching anything from before 1960 – honesty, you can understand them without leaving genre fiction (watch Blade Runner, play Disco Elysium). It's about a heightened use of lighting and visual contrast. It's about the question of what it means to live a moral life when your individual actions don't matter very much. It's about an aesthetic of decay that looks back to the Romantics, while doing them one better by either a) exploring clean decay, b) considering the aesthetics of deliberate destruction, c) imagining the decay of the future – any, all, or more; what matters is the twist, the vision of a decay that has nothing to do with nature.

Noir lends itself extremely well to stories that are dubious, at best, about capitalism and the carceral state. These stories don't trust most people to act correctly, and by extension, they tend to critique systems. It follows that one moral question they examine is this: if the world is fallen – if there's no ethical anything under anything – and if an individual can't fix this, how can we find meaning in good acts? Here are the ways that four excellent films, and also Odd Man Out (1947), consider this question.

Double Indemnity (1944). Double Indemnity takes a form dear to my heart: the crisis hotline call. Corrupt insurance salesman Walter Neff narrates a murder confession to his co-worker's Dictaphone as he slowly bleeds out. See, weeks ago, Neff met a woman who wanted her husband killed, and he got rid of him for her, seduced both by her beauty and by the vision of himself as a mastermind. In actual fact, Neff is dumb as rocks and being played by everybody. Double Indemnity is credited with codifying the noir genre, and was cowritten by Raymond Chandler. Its Boschian vision of a universally exploitative world will be tuned more finely later, but its ideas about how that world works – that is, the person most open to exploitation is the one who thinks they're doing the manipulating – are already fully developed and in attack configuration.

How homoerotic is it? Pretty homoerotic. I've gone back and forth with family and friends about Edward G. Robinson's character, an insurance investigator (everybody in this film sucks) and the recipient of Neff's confession. In the end, I remain convinced that he's extremely queer-coded and extremely in love with Neff, and his story about ruining a long-ago engagement is the best kind of cover, i.e. one that doesn't require him to hurt an actual woman. The film ends with Neff in his arms, and the lighting of a charged cigarette, as the characters' mutual understanding is revealed as the only good or human thing they've ever done. Romance.

The Third Man (1949). While Double Indemnity deliberately sets itself in the late thirties in order to avoid thinking about World War II, The Third Man is obsessed with the war. This film is a vicious critique of America's fantasy of innocence – the idea that America, merely by virtue of opposing fascism and being very far away from Europe, is as clean as the toothpick that shows a fresh cake is ready – and it did it before the ringing of bullets and propaganda had left anyone else's ears.

Like Double Indemnity, it's about a guy doesn't know that if you can't spot the pigeon at a card table, you are the pigeon. Holly Martins has a more innocent mission than Walter Neff – he's traveling through postwar Vienna, trying to find out what happened to his dead friend Harry Lime – but in the cosmology of The Third Man, that kind of thing makes you much more dangerous than a simple guy who does a simple murder. Lime is a Gatsby who's cut out the middleman, a black marketeer whose dangerous goods have claimed lives, and Martins goes through most of the film deliriously drunk on visions of their shared childhood, which in his mind makes Lime's obvious corruption admirable, even cute. The striking thing about Martins' inevitable recognition that he sucks – that his country has stretched a cheeky grin over an empire as hideous as any – is that nobody else in the film wants him to get better. They want to preserve his dream of innocence, not because they care about him, but because he's so nakedly messy and unpredictable that they have no idea what he'll do otherwise.

The film is anchored by insane performances from Joseph Cotten as Martins and Orson Welles as Lime. If I have ever seen a better movie, I can't call it to mind right now.

How homoerotic is it? Actually as un-homoerotic as a film can be in which one best friend mercy-kills another. I believe Lime and Martins love each other very much; I don't believe they've fucked or want to. This is partly, I'll admit, because Welles is deliberately costumed so as to seem disembodied – he is clad in voidlike black, in a swishing, swirling coat, above which his face floats as an emptiness – which may have been a matter of the director wanting him to look thinner, but which I prefer to read as a signifier of Lime's spiritual amorphousness, the way he assumes the shape into which he's poured, like black oil with a rainbow sheen.

The director in question, by the way, is Sir Carol Reed. Fuck yeah, Sir Carol Reed!

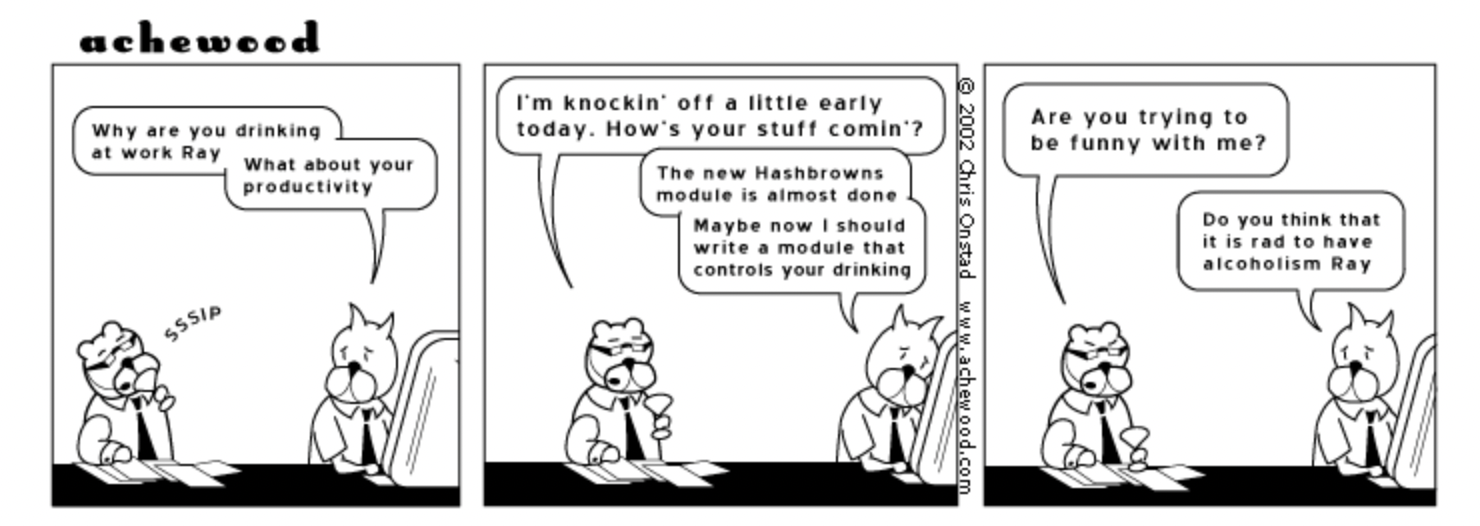

The Lost Weekend (1945). So Wikipedia claims this is a noir. Wikipedia tends to declare anything a noir if it's in black and white and kind of a bummer, but this was made in direct response to Double Indemnity – basically, it's director Billy Wilder trying to process what it was like to work with the alcoholic, depressed Chandler – and does feel undeniably noirish, although it lacks a detection plot, or much moral angst, or even visual showiness (it shared a director and cinematographer with Double Indemnity, so it's not like they couldn't have drenched it in chiaroscuro if they'd wanted to). Famously, it's about an alcoholic would-be writer hitting bottom. The writer is played by Ray Milland, which allows me to just summarize it via this Achewood:

How homoerotic is it? I've skipped to this part early because The Lost Weekend's main problem is that it's not homoerotic. It's based on Charles R. Jackson's harrowing novel of the same title, in which it's explicit that the hero's drinking comes from the grinding corrosion of the closet. To my mind, this complete heart amputation undoes the film, although Milland and his co-stars are very good. Blame the Hays Code, RIP.

Odd Man Out (1947). Some say that this is Carol Reed's best film. Some are, I think, being pointless contrarians here. Are you ready for James Mason as the head of the IRA, except that Reed chooses never to name the IRA, and in fact to make Mason's character's backstory extremely vague, even to the point of including a title card explaining that this isn't a film about political conflict in Northern Ireland, but a film about the effects of conflict on the human heart? Are you ready for a cast who mostly die in reverse order of Irishness? Perhaps you're ready for Odd Man Out, which also wins the award for most vaguely titled movie I've seen this year. It could be anything from an Adam Sandler comedy to a war film about an entrenched unit's beloved mascot, Patches.

The weird thing about Odd Man Out is that its second half kind of fucks, after Reed and writer R.C. Sherriff have largely abandoned the plot and turned their camera to increasingly wild sequences of Mason – whose character has emerged from prison anxious and agoraphobic, before being shot at the beginning of the film – lurching through Belfast bleeding and hallucinating. Like The Lost Weekend, it uses primitive special effects to bring fantasies and hallucinations to the screen, though while The Lost Weekend uses them to show the actual poverty of its hero's imagination (he sees booze), Odd Man Out gives Mason's character (okay, okay, his name is Johnny) a vivid inner life. This life spills out as the kind of charisma that makes everyone want to help him, harm him, or shoot him again. Mason takes the concept of the noir patsy to its logical conclusion: rendered empty-eyed and docile by pain, Johnny exists to be the object of different people's moral angst, even as most of these encounters end by default, with Johnny staggering away before anyone can make a positive decision.

Once again, though, we have a film undone by the refusal to look at something. It's all right to make a story about the human heart. It's just that it has to flail so furiously to avoid asking actual questions about colonialism, political violence, and the history of the English in Ireland that by the time we get as far as anyone's heart, the whole thing makes no sense. It is incredible that Reed went on to make The Third Man two years later; perhaps he learned from his mistakes, or perhaps it's just easier to critique another empire than yours. Also, it's the one noir on my list that actually does argue that individual acts are really important and can change the world. It just doesn't think you should do them. I'm not even talking about all the questions and issues which Odd Man Out avoids. I'm talking about total nihilism.

How homoerotic is it? Not homoerotic.

Sweet Smell of Success (1957). I told Calvin that the work Burt Lancaster is doing in this film belies the fact that he's called Burt, to which he pointed out, "Burt is one of those old names like 'Ethel' that used to mean you fucked. Once upon a time that guy was the most famous Burt, not the muppet." I am forced to concede his point and apologize to the world's Burts. Sweet Smell of Success came much later than the other films in this newsletter, and you can tell; among other things, director Alexander Mackindrick and his co-writers are now pushing the envelope of the Hays Code like fighter pilots at Edwards AFC. Tony Curtis (silky, beautiful, trash) is a PR flack and henchman to a gossip columnist whose whims make or destroy careers, played by Lancaster (languid, corrupt, capable of punching a man's lights out in a bored way). Curtis is great, Lancaster is magical. It's one of those performances that are played entirely on one string because the actor doesn't need any more. Everything Lancaster does in this film is so funny, disturbing, and surreal that the performance should by rights be All About Eve famous.

Anyway, if Double Indemnity argues that in a garbage world, all we can do for one another is listen – if The Third Man argues that in a garbage world, all we can do for one another is know what we've done – if The Lost Weekend argues that in a garbage world, all we can do for one another is recognize that self-destruction isn't a victimless crime – if Odd Man Out argues that in a garbage world, there is nothing at all that we can do for one another – then Sweet Smell of Success argues that in a garbage world, one in which rival gossip columnists roam the earth and joust like kings, all we can do is disengage. The film has heroes, though they're not the main characters; they're the people (Lancaster's abused sister and her fiancé) who ultimately get the fuck away from the main characters. It ends with the equivalent of getting off Twitter. I think that's beautiful, and I recommend this horrible masterpiece as highly as anything on my list except for The Third Man, which you owe it to yourself to see before you die.

How homoerotic is it? If Lancaster and Curtis' characters have never slept together, then I am not alive.