That Massive Islet of Guano

(Previously on badasses and their uses.)

I just finished William Battersby’s James Fitzjames: Mystery Man of the Franklin Expedition. Fitzjames was the third-in-command of Franklin’s doomed trip to the Northwest Passage, a beloved naval officer whose comic-opera adventures belied the fact that he’d conned or spent his way into his promotions to midshipman, lieutenant, and commander. His life was absurd from birth. On every page of Battersby, he is taking off his pants to fit into a canoe, giving a polished drag performance, writing a bad epic poem, defending an island covered in a seven-meter-thick blanket of bird guano, indulging in expert disguise, shaking off a supposedly domesticated cheetah, or pulling an honest-to-god Fitzcarraldo on the coast of Syria. Reading the book makes one feel like Nick Carraway, presented with Gatsby’s war medal: “Then it was all true. I saw the skins of tigers flaming in his palace on the Grand Canal; I saw him opening a chest of rubies to ease, with their crimson-lighted depths, the gnawings of his broken heart.”

In sum, Fitzjames was a badass, a figure I despise. The word encompasses a kind of heroic flailing, an essential fuckuppery which — combined with main force and good intentions— sees the character through. Harrison Ford plays a lot of badasses, who are all placed in opposition to empires to disguise the fact that they serve other empires.

The reason a badass is an imperial figure, though, is not just imperial service. It’s that he represents the way empires see themselves: a lovable fuckup. An innocent figure, with guile but without the capacity to plot — he has no need of skill or expertise beyond his own common sense and know-how. He can walk into any situation and understand it better than the locals. (I’m giving up and using he/him pronouns here; although the archetype can adhere to any person or character, it is deeply bound to a specific vision of masculinity.)

The badass is a traveler, and the names of the towns or cities or countries he visits become his styles, his titles. A city of a million becomes an ornament for the hair. Before Fitzjames shows up to play his part in The Terror, Francis Crozier scoffs at his endless stories of “policing that massive islet of guano off the coast of Namibia, or the time he got shot by the Chinese.” He makes it sound like “Sympathy For the Devil,” and the biography reads like “Sympathy For the Devil,” and in fact it’s very easy to interpret “Sympathy For the Devil” as an indictment of this whole vibe. Certainly, like the characters in Luke Haines’ gentler “All the English Devils,” a lot of work is done to establish Satan as an English gentleman, or in Haines’ case at least an English con artist (“British traitor”).

Anyway, I can’t hate Fitzjames. Besides the fact that I’m a citizen of empire too and have no grounds to criticize the delusions he represents, he is also extremely dead. More importantly, the badass is never the same as a real person. The character exists to project shame outward and make it fun. In the case of the biography, the story is filtered both through Fitzjames’ semi-joking boasts and Battersby’s passionate investment in him. (God, remember Battersby? That was three paragraphs ago.)

This investment is the fatal flaw, by the way, in Battersby’s boisterous and very funny book. I’m familar with books like this from my years as a massive Titanic head: extraordinary archival shovelwork by authors with an axe to grind. Battersby is all right when he’s detailing Fitzjames’ exploits (what a word), and the rich deposits of humor and sensitivity that made his life livable. It’s when he stows the shovel in favor of the axe that things get rough: he is incapable of admitting that Fitzjames was out of his depth planning an expedition to Arctic, and that Fitzjames died of this, along with many others.

But the fact is indisputable. Yes, Fitzjames had bad luck; no, not all bad luck can be countered by good planning; yes, many deaths from bad luck are deaths from hubris. There were various collaborators in the expedition’s abject failure, including the other captains, but Fitzjames did minimal research, displayed a deep unseriousness about the project, was cheerfully casual in selecting officers who included a suprising number of his war buddies, and was only chosen for the expedition because he’d saved a powerful man’s son from blackmail. And this stuff is in the book. To counter any bad impressions, Battersby explains that unlike the officers of the Titanic sixty years later, Fitzjames was careful about icebergs.

Anyway, I obviously became interested in Fitzjames because he’s a major character in The Terror, in which he is redeemed the only way a badass can be: he is stripped of his titles and killed. In this, I wish to separate the death of Fitzjames the man (wretched, undeservable) from the death of Fitzjames the character (a tragic masterpiece) from the death of Fitzjames the badass (a stripping-away of the extraneous; a laying bare of a self that represents nothing; what Fitzjames the character soberly calls “the end of vanity”).

I don’t suggest that we kill our love for the badass. We can’t do it, any more than we can kill imperialism or pleasure; suggesting that we solve a problem by killing a pleasure would be an even more fucked-up approach. But every time we strip a badass of his powers, we take pleasure of a different kind, and I recommend this joy above the joy of watching him work.

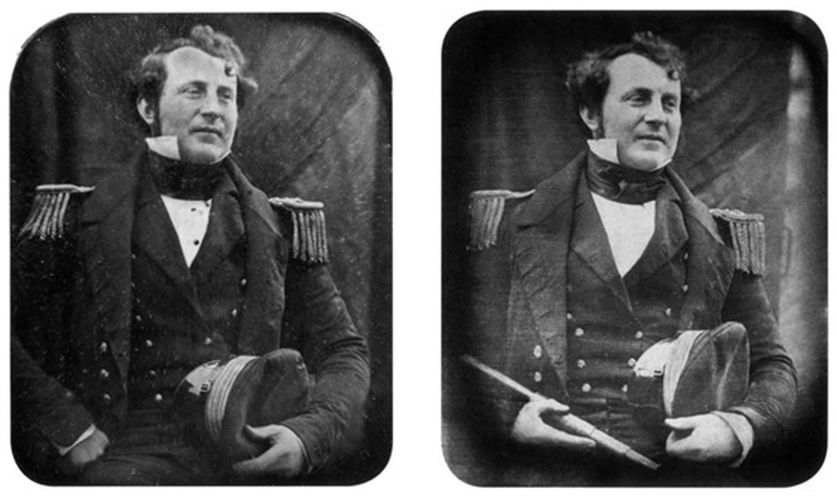

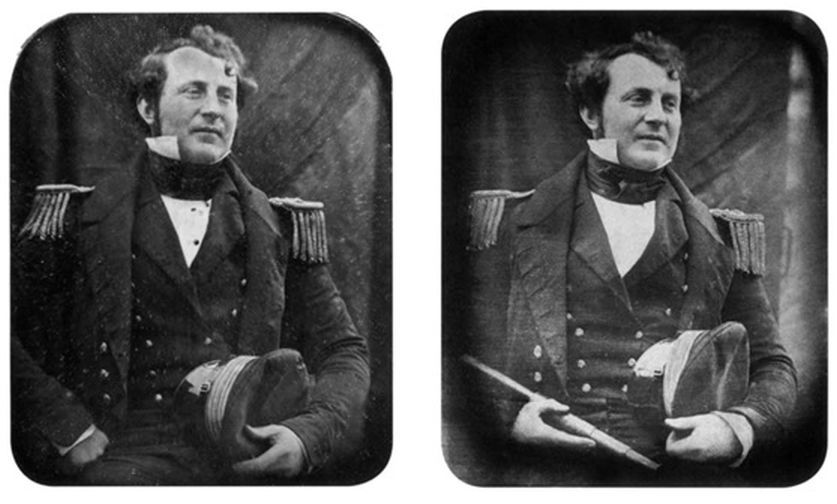

(Image source: Scott Polar Research Institute.)