The Bottom Energy of Nam June Paik

There's a massive Nam June Paik retrospective on at SFMOMA. Paik, a Korean-Japanese-German-American who's most often described as a "video artist," was totally unknown to me when I walked into the show today at 11:00. By 11:05, I was mentally describing him as "my beloved, my mad lad Nam June Paik." By 11:15, I would have died for him.

Paik's work is a rare combination of humor, unpretention, and intellectual and emotional rigor. For most of us, it's hard to be rigorous without being pretentious, or funny without losing sight of emotion. I say this without any value judgement. Pretention is an important tool for pushing yourself past your ordinary limits. Many kinds of humor rely on a temporary, contractual heartlessness. Most of the time, we accept a little loss – of heart, of perspective – in art if the results are good. But Paik's work is a lossless recording. It's uncompressed, a .FLAC file.

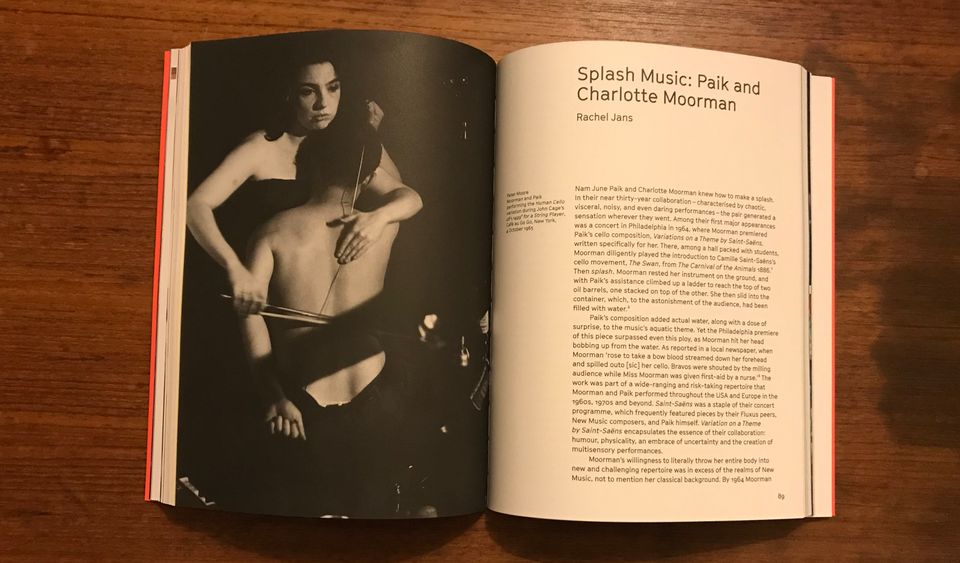

He also had tremendous bottom energy. In the exhibit is a poster of Paik with his frequent collaborator Charlotte Moorman, a cellist and avant-garde figure for whom he constructed things made out of televisions: a cello, a pair of glasses, a bra. (Much of Paik's career revolved around fucking around with tube televisions; his most famous piece, TV Garden, places forty of them at odd angles in a jungle of plants.) Moorman was famous for performing nude or partly nude, for which she was arrested onstage at least once; in Paik she found a collaborator who was also trained in classical music and composition, and was also interested in playing it while naked. The exhibition's text specifically says that the two of them wanted to reintroduce sexuality to classical music. Plenty of people have tried to do this, of course, but mostly they just land on making it ~erotic, which is very different from making it sexy. "Erotic" is a woman's naked back, painted with the f-stops of a violin. "Sexy" is this poster.

Paik is photographed with his naked back to the viewer, a cello string gripped in his fists and stretched taut from his shoulder to his hip. A clothed Moorman is leaning over him, playing him as a human instrument. The image is sexy, not ~erotic, because it's collaborative. Paik's whole body conveys enthusiastic willingness to be exactly here, gripped in the fabric of Moorman's skirt, using strength alone to create the steady tension that allows her to play.

In addition to fucking around with televisions, Paik was obsessed with building robots, many of them memorials to dead friends or tributes to living ones (a project he called "Family of Robot"). His work doesn't center on the typical connotations of machines. In one manifesto included in the exhibit, he writes, "I make technology ridiculous." By ruining televisions with magnets or placing them in weird, organic settings, he makes them dopey and absurd, objects whose dignity is revealed to be very situational. And in becoming a machine for Moorman to play, he makes himself ridiculous too – which is to say that he makes himself tender.

It's a splendid bottoming performance, in other words. Paik doesn't let Moorman do things to him; he asks that they be done. He asks her to thrill him. You can see the thrill of that collaboration all through the exhibit room dedicated to their work together. Here is her television cello, which they worked together to make playable. Here are her electronic glasses, the water barrels she used to jump into mid-performance. Here is the absence of her artist's body, in the sculpture and collage Paik made to mourn her premature death from cancer (Paik was seemingly doomed to outlive his friends). It's obvious that Paik adored and admired Moorman, and that the center of their work together was his wish to help her succeed.

It's an axiom that plenty of great art is made by bad people. I don't actually know if Paik was a good man or not – just as I don't know what he was really into in bed – but it is obvious from the show that he loved to collaborate, and had no shortage of brilliant friends to collaborate with. Moorman, John Cage, Merce Cunningham: he wanted to see what happened when you smashed different talents together, often across the lines of visual art, music, and dance.

Artistic collaborations don't absolutely need "topping" and "bottoming" per se, any more than relationships do, but it does help to know yourself: what you want to do, what you want done to you, whether you see yourself today as a facilitator or a star. The joy of the Paik show is watching him lovingly humiliate different pieces of technology (burning a candle in a hollowed-out TV; running TV shows through a "video synthesizer" or a hand-drawn "paper program"), but it's also in watching him submit (creating bizarre pianos for gallery visitors to play; watching Cage jump into the fray and take an axe to one of them). It's worth mentioning, also, that the man clearly fucking loved television, not just televisions. "TV Garden," which incorporates programming from worldwide sources, is a straight-faced vision of international unity. With regard to TV, I think he's best described as a switch.

Paik also didn't lack for ego. One of the most beautiful pieces in the show is "Sistine Chapel," a jumble of projectors playing semi-random sounds and images in a vast white room; in it, Paik not only claims the role of Renaissance master, but demands an enormous space for his work. But you need ego, I think, to bottom really well. You have to know your own power to know how to give it up.

Are you one of the people who subscribed to my Substack in the past couple of weeks? You should know that I've stopped updating that newsletter because I've moved to Ghost, but I've automatically added you to my mailing list over here! Please don't be alarmed or adjust your dial, unless of course you, like Nam June Paik, enjoy turning televisions on.