Who's Afraid of Virginia Prince

Transvestia was a small magazine for crossdressers which ran from 1960 to 1986, mostly under the aegis of the same brilliant and despotic editor, Virginia Prince. I'm using the term "crossdressers" with intent here, because this is how the people who subscribed to the magazine identified. Specifically, they were "heterosexual male crossdressers" – no gay or bisexual men, nobody who dressed as part of a kink, and ostensibly no trans women, although I'll hazard that Tranvestia's audience were virtually all trans women. It's just that Prince's subscribers didn't see full-time womanhood as a possibility, in a time when transition was rare, unevenly available, and entailed the risk of losing everything, even more than it does today. As a result, they turned to the page to express themselves.

When I arrived in trans community in 2019, I was aware of Prince as a person with what's called a "complex legacy," but I didn't really know why; everyone else seemed to find it self-explanatory. Since I've begun reading stacks of Transvestia for an upcoming project, I've begun to understand her better, and to feel that special, aghast admiration that Americans feel for grifters. Prince was pulling down cash from Transvestia; in the early 1960s, one issue cost $4, or about $40 in modern dollars. That's not including the money she made from selling breast forms and lube, or setting herself up as a middlewoman for subscribers who wanted to order wigs from LA. By her own account, the magazine struggled financially in its early years, but I have difficulty understanding how that's true; Prince didn't pay contributors, and the magazine was cheaply printed (though it always had an attractive cover, generally featuring a glamorously dressed subscriber). It's like paying $40 for a zine.

Even if I'm wrong about the money, and I don't think I'm wrong about the money, Transvestia was a grift. It sold an illusion – the idea that the desire to be a woman could be controlled and tamed, with the help of an understanding wife and a serious reading of Jung. The idea was that, if you weren't attracted to men, avoided all thoughts of medical transition, and instead focused on the idea of achieving Full Personality Expression (FPE), you could live a happy life, your animus and anima in balance.

FPE was one of Prince's many neologisms. She also called herself a femmiphile, or FP, and encouraged her subscribers to identify as FPs as well. In this, she recalls nothing so strongly as one of those fans who in the 1990s and 2000s would get a stranglehold on a small fandom and make it their personal fief, with various shibboleths and mandatory beliefs. Like this kind of high-profile fan, Prince expected complete agreement, told wishful half-truths about herself, felt persecuted by everyone. The thing that separates people like this from con artists is the nature of their desire. Prince never rolled out of bed and thought, "I'm going to exploit other trans people by presenting them with a delicious fantasy of non-transitioning female life." This is a woman with her own damage. She was traumatized by being very publicly outed during a divorce, perpetually trying to figure out her own life and place in the world and what femininity meant to her (she herself started living as a woman full-time in 1968). She plainly felt that she was owed – as indeed she was; all of these people were owed more than they got.

Of course, it's important to draw a distinction between cross-gender desire, which has existed for as long as people have, and contemporary trans identity, which is just one of the many faces this desire has worn. In describing Prince's subscribers largely as thwarted trans women, I'm aware that I'm being a bit ahistorical, and dismissing the way that they actually identified – as crossdressers or FPs. At the same time, I can't describe enough how much this magazine vibrates with the contributors' longing to live as women. The fantasies are painfully simple, the victories painfully small: a breathless recounting of a shopping trip en femme, an autobiographical account of a painful childhood which suddenly veers into an obvious fiction about the first forays into cross-dressing being approved and admired by the whole family. Prince's subscribers are modest dreamers. It's astonishing how little they want.

Transvestia's articles are a potent mixture of encouraging truths (the wife who has come to enjoy her spouse's "hobby," and now shares makeup tips with her) and dreamy, extravagant fantasies (the wife who runs a charm school, and has given the FP a thorough education, even showing her off to her students as a demonstration of what careful study can achieve – though this might be a bad example, as I actually kind of think this one was real). Gowns, underwear, and wigs are sensuously described. Sometimes Virginia, who has a PhD in pharmacology, reprints and snarks on a scientific article. The letters column is often the best part – my favorite letter so far is a break from Transvestia tradition, in that it's shamelessly kinky; in it, a wife describes her enthusiasm for her partner's cross-dressing, the fact that they run a business and have a lot of private downtime, and basically spend it all wearing cute dresses and doing capital-B Bondage together. I believe completely in the Bondage couple, and I hope they died at the exact same moment at the age of 100.

In sum, the magazine was a heady, richly perfumed substitute for womanhood. You subscribed to it to keep going, to keep convincing yourself for one more day that your desire couldn't be fulfilled, but that that was okay – you didn't really have that desire, anyway. You were just balancing your humors; you were just walking the line between what you wanted and what the world expected of you, as a person living as a middle-class-to-wealthy man (the kind who could afford this magazine).

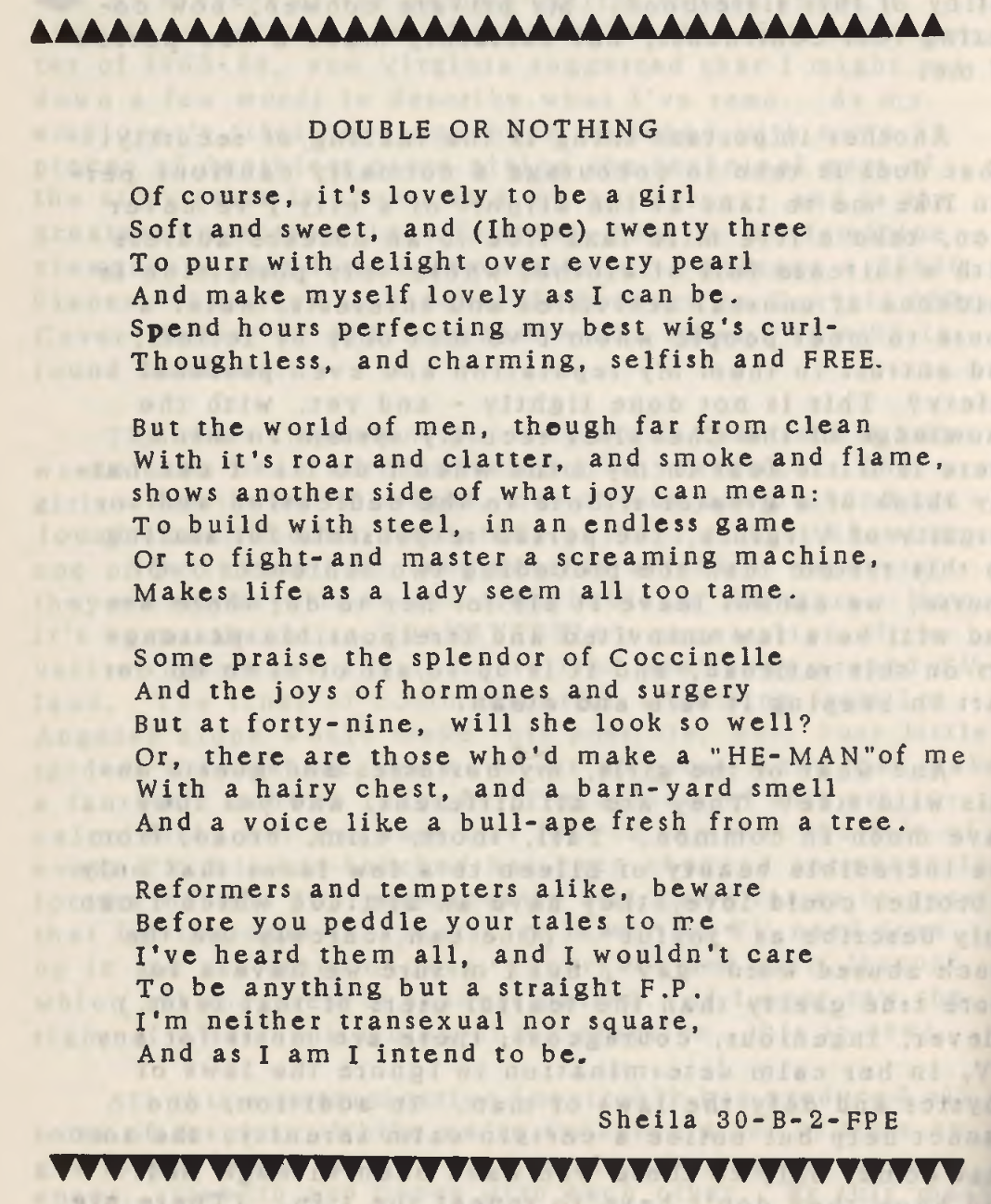

Transvestia makes its class expectations clear. Everyone in it is expected to be a lady, a hostess, a woman of the same class as the ostensible man she is outside of the house. (Transition would entail a drastic loss of earnings and drop in class, but this way, a girl can have it all.) And, honestly, I get it; of course someone like this would be anxious about the few trans women they see in the news, all of whom seem to be doing sex work, or at least are some kind of professional entertainers. Transvestia's subscribers came from a culture which saw that work as abjection. Of course they didn't want to be abject, and if that's what transition meant, well – no. There is a remarkable poem in one issue I recently read, which is worth reprinting in full:

Not to be a bitch, but I actually take issue with the idea that this poem is neither "transsexual" nor "square" in content. I mean, why not both? More to my point, though, it expresses an anxiety about identity that's central to Transvestia's project. There's a real struggle with masculinity on the one hand (that "screaming machine"), with femininity (wouldn't it entail a more retired, quiet life than Sheila really wants?), and with the idea of transition (against which Sheila's main argument, painfully, is that she feels too old). Hard though she tries to find pleasure, the options available to Sheila are all bad. All of them entail a palpable loss of freedom, safety, and class status – so she chooses none of them, and is proud of it. That's the Transvestia way.

Transvestia is a tremendous document, full of pain, humor, and humanity. It is what the academics might call a "technology," by which trans people can transmute their pain into intellect and pleasure, and express and embellish their moments of joy. In addition to a technology for avoiding transition, it's a technology for transitioning, albeit only in fantasy. I hope that none of the criticisms I make above, which I realize are significant, detract completely from how much I love this magazine, and how much it helped its subscribers. Prince's argument – that you can have everything if you settle for nothing – is potent, and I'm genuinely sure it saved lives. It's just that I wish someone had really asked Sheila whether she wanted to consider hormones, as a positive choice, and in a world dreamier than anything in Transvestia: a world where it's safe to be trans. I wish I could know what she would have said.