Songs our parents preinstalled

Each of us ships with a suite of built-in music. It’s the stuff your parents played in the car before you were old enough to complain — music that imprints on you like a greasy thumb. I imagine it comes on an old mp3 player, the kind that now connects to no earthly computer, but still manages to charge. You can like it or not, makes no difference. It’s in there.

I never asked to memorize the complete works of James Taylor, the original Broadway cast of The Phantom of the Opera, or the Eagles’ Hell Freezes Over. My musical taste has exactly two things in common with my parents’: we tend to get hung up on one album for an extraordinary amount of time, and Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms.

There is admittedly some annoying shit on Brothers in Arms, which flew past child-me like Cleopatra’s rosy-sailed yacht. The sneering, homophobic narrator of “Money For Nothing” is a Microplane for the ear, although unlike (say) the narrator of the Eagles’ “Get Over It” (“Bitch about the present!/Blame it on the past!/I’d like to find your inner child and kick its little ass!”), you can tell the singer is doing a bit. “So Far Away” is a kit-assembled “I’m on tour and you’re at home/baby, it’s Man’s Fate to Roam” song. Actually, the album is front-loaded with this kind of self-indulgent noodling, interrupted only by the slinky four a.m. vibe of “Your Latest Trick.” In its second half, it takes an abrupt, straight-across-traffic lane change, fishtailing and lurching with thwarted inertia, into an apocalyptic three-song cycle about war (??).

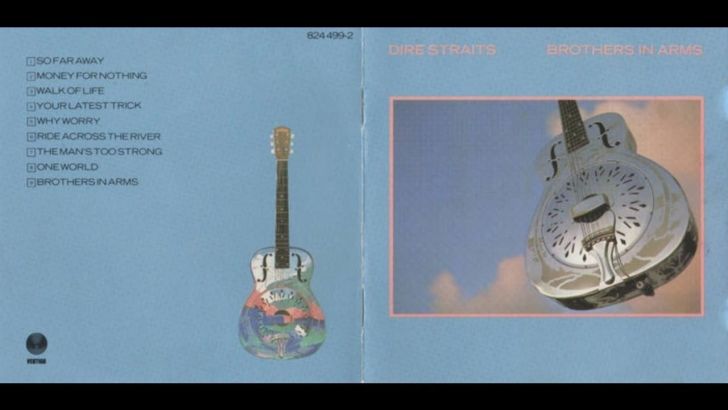

What unites these two moods is a liquid-satin smoothness, a clean stack of saxophones and synthesizers and drums (I looked this up, and they’re somehow not drum machines) upon which Mark Knopfler sits with his guitar, vibing like a cartoon lizard. It sounds like an engineer’s hallucination, following ingestion of a very conservative amount of drugs. It sounds like the first CGI, green lines and metallic pyramids floating in space. Hell, even the cover looks CGI, with Knopfler’s silver guitar hovering in front of a cloudscape, held by no expensive-to-animate hand. Brothers in Arms is the simmered reduction of the eighties — the machined precision, the glowing lines, and the massive empty spaces in between everything, where information ought to be.

Given all this, it really is weird that the album gets drafted at the end. But it does, and it has a highly specific vision of war — abstract, staticky, stateless. In “Ride Across the River,” Knopfler is crisp and disengaged as he tells the story of a young soldier turned mercenary. The war criminal’s confession in “The Man’s Too Strong” is done in veering swings, economical and perfectly timed. Even the title track, which initially sounds like a hushed tribute to a sort of Greatest Generation situation, is a dying man’s plea for peace. It’s televisually extended, with a dramatic Powers of Ten zoom-out into the galaxy (“there are so many different worlds/so many different suns/and we have just one world/but we live in different ones”). It works, though, because Knopfler delivers it without sentiment, with no aid but simple sadness.

Maybe that’s why I love this arid, cynical album about missing loved ones and never sleeping and watching lots of TV: it doesn’t work too hard to convince you of things. It’s opinionated, sure (MTV: bad! your latest trick: effective, but pretty low! making war on our brothers in arms: foolish!). But its sub-zero chill keeps it from being polemical. It’s a case of two unappealing types — the crank on the subway, the guy who smoothly hits on you on the subway — singing in surprisingly powerful harmony.

I want to save my last dance for “The Man’s Too Strong,” one of the two songs on Brothers in Arms for which I will go to bat for real. The song is a final confession by a dying dictator who veers back and forth between exalting and denouncing himself. Neither attitude is much more than a manipulative pose. The song’s overriding emotion is self-pity, that’s all. But here, give it a listen —

That chorus! Some of its power, admittedly, depends on whether you see one narrator or two. It’s easy to read “I can still hear his laughter, and I can still hear his song/the man’s too big/the man’s too strong,” with its coups of thunder and lightning, as a switch to the priest’s memory of the confession. But to me, it’s obvious that this line is the dictator’s, too. He’s dying, and underneath his self-serving patter about being “just an aging drummer boy,” he senses a deeper, a truer evil, a historical force pursuing him through life, dragging him now into hell. “The Man’s too big,” he cries helplessly, “too strong.”

It’s an eighties album, and therefore it’s a dispatch from the end of history — from a time when many Americans were trying to pretend that they had passed out of history, straight through the present, and into the future, with computer fonts and sci-fi colors and nobody dying. Of course, this fantasy was a Halloween mask over an actual skull (go read Maxe Crandall’s The Nancy Reagan Collection), but I’m sure people knew that. Brothers in Arms was a giant hit, and it was imbued with everything the eighties liked to see, but you can always see reality peering through its shiny eyeholes.